If you have been following the discourse over the proposed changes in the Barbadian education system, you might have observed that the debate has split into two ostensibly equal factions. There are the ‘reformers’ on the centre-right of the spectrum and the ‘transformers’ on what one might call the centre-left. Most centrists, if you can call them that, agree on some need for change. The dividing line seems to be between those who oppose the abolition of the 11-Plus and are against the two-tier system in the secondary school structure.

These ‘reformers’ suggest that there is some need for an exam at age 11-Plus if for no other reason than to give children something to aim at. Beyond the primary cycle, the reformers contend that any substantive changes could be effected within the existing secondary structure and generally warn about the possible disruptions likely to be created by a problematic two-tier structure. On the other hand, there are the more radical root and branch transformers who support the abolition of the Barbados Secondary Schools’ Entrance Exam (BSSEE) and anything remotely resembling it, and defend the two-tier structure post-age 11.

This difference is not surprising. Some years ago, a survey showed that if 50 per cent of Barbadians wanted to abolish the Common Entrance Exam, the other 50 per cent wanted to maintain it. The debate is understandably heated because it involves people’s children and their futures. Although few might want to admit it, it is also a discourse loaded with colour and class affiliations.

In an interesting critique published in another section of the press, David Hinkson begins by quoting a Johnny Nash hit which states: “There are more questions than answers, and the more I find out the less I know.”

It is amazing that for a proposal that is supposed to go before Parliament sometime in January 2024 and a reform that is slated to start in September 2025, so many gaps still have to be filled in. What would we be going to Parliament with? Certainly not just with the brightly coloured, nicely presented booklet on ‘reimagining’ that has been presented to the public.

As with many notions of education reform, there is much jargon that sounds good but, as Hinkson says, leaves a lot to be explained.

The Chief Education Officer is quoted as saying: “Children will leave primary school with a personalised profile determining their strengths and weaknesses, which is to guide educators in prioritising individual need over traditional subject-based teaching.” One hopes that the chief recognises that a prime need of the child is to leave primary school with a firm grounding in basic numeracy and literacy skills. That is the basic premise on which primary or elementary schooling is based.

The chief’s statement sounds like something out of a scholarly educational journal, but as Hinkson asks, “What does this really mean in the real world? How will this profile be done and how does it determine where my child ends up? Besides, in a class of over 25 students, beyond the verbiage, how does one class teacher prioritise ‘individual need’ over ‘traditional subject-based teaching?” Certainly we cannot preempt or minimise traditional subject-based teaching. It all sounds good, but what does it mean in the context of the actual classroom? Besides, this seems like a lot more work for already burdened schools and teachers. And for the Lord’s sake, be very careful how you profile and position people’s children. It all clearly suggests that there will be a number of tests somewhere around age 11. The journalist quotes someone as saying that “this sound as clear as mud”.

As with any politically inspired document, there is a lot of gloss. Ordinary schools will all become ‘academies of excellence’. The notion of a ‘middle school’ has disappeared from the lexicon to be replaced by junior and senior colleges. Hinkson reminds us how a late Education Minister Cyril Walker’s notion of a 14-Plus exam evoked almost universal disapproval. The notion of specialised schools is always attractive but few children know with any degree of surety what they want to do at age 14. We have to be careful about pigeon-holing children too early. The reimagining document offers parents appellate rights. A Ministry of Education already facing a multitude of issues could find itself swamped with legitimate and frivolous appeals.

Hinkson’s article posed the appropriate question: “Transformation – too much too soon?” The structural alterations proposed for the Barbados Education system are too complex to be rushed but someone, somewhere wants it done – like yesterday.

There are five structural issues plaguing Barbadian schooling leading to inefficiencies and diminishing outcomes.

Underperformance at the primary stage. As one person suggested in Hinson’s article, it might have been better to look at pre-primary and primary schooling first and by itself rather than attempting such massive change all at once. But this might not have satisfied somebody’s messianic vision of transformation.

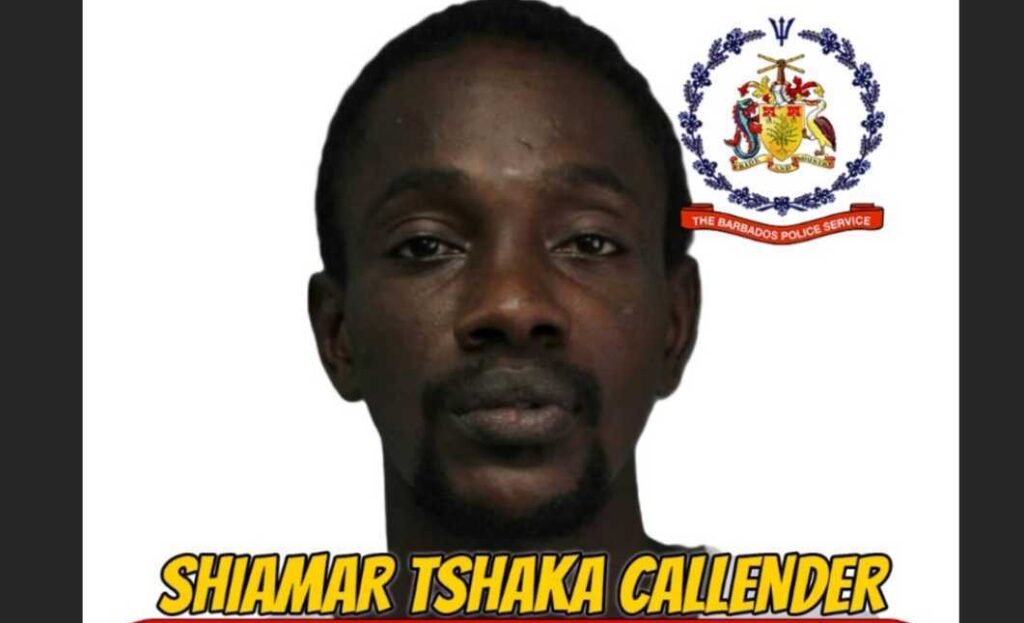

Barbados needs to determine what schooling is best suited to those children who clearly have not mastered the primary curriculum by age eleven. I suggest a limited curriculum with continuing emphasis on improving literacy and numeracy inadequacies, with emphasis on more manual-vocation creative pursuits that might be of interest to those students. There must be greater emphasis on character building for children observably at risk at that stage to save them from themselves and ultimately to save society from them. As someone once said, if we do not develop children’s abilities, they will become liabilities. Witness the recent attack on two elderly ladies in broad daylight.

Barbados does not need two new secondary schools of the existing type. It needs two other institutions. Firstly, there is an urgent need for a trade school catering to those students, boys and girls, who may never acquire the academic type qualification needed to get into the Barbados Community College or the Samuel Jackman Prescod Institute of Technology. These students invariably have an interest in and a talent for something. We must get away from the traditional tendency to privilege academic schooling above all else.

Barbados is throwing up a growing number of at-risk children who, if not catered to, will continue to prove a problem to society as a whole. We need to look seriously at reform education, residential and otherwise.

Finally, Barbadian society is showing signs of psycho-social decay. If we are going to save and transform education, we will have to change society as a whole. That is an incomprehensibly difficult matter.

These are the real challenges facing Barbadian education at the moment.

Ralph Jemmott is a retired educator.

The post A Conflict of Vision appeared first on Barbados Today.